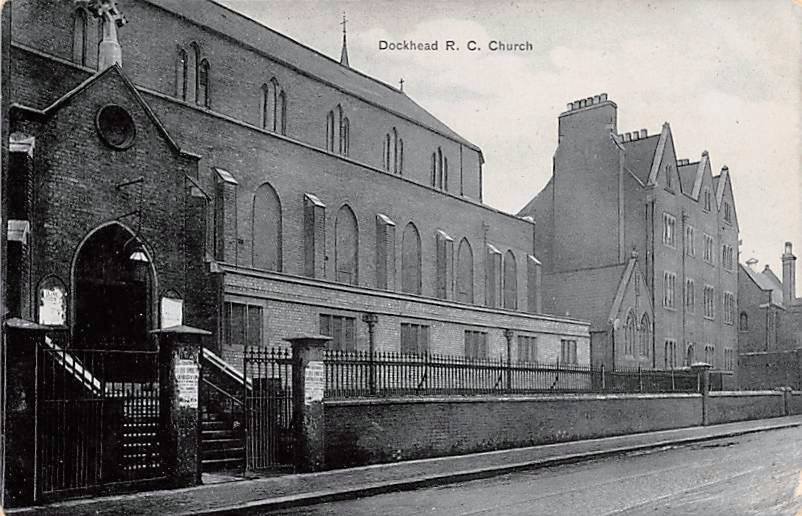

The Church of the Most Holy Trinity is the Roman Catholic Parish Church of Dockhead.

Dockhead is an area situated just north of Jamaica Road in Bermondsey and runs east/west just south of Tower Bridge. Named to describe its geographical position at the “Head” of the London docks on the South side of the Thames, Dockhead was home to the Dockers, Stevedores and Lightermen who worked in the Docks up until their demise in the 1970s and 1980s and in terms of my family history, home to most of my Mother’s family during the nineteenth century and up until the Docks’ decline. I lived just off Jamaica Road not far from Tower Bridge when I was a child in the 1950s and my Dad and several of his brothers all worked in the London Docks.

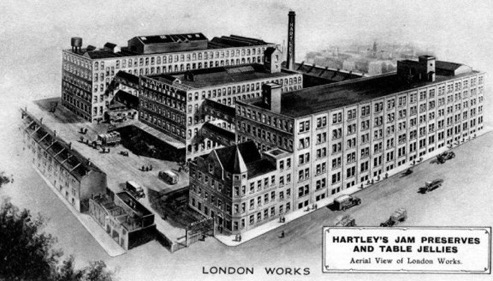

The Docks were known as the ‘larder of London’. Everything came through these Docks, frozen meat, spices, tobacco, wool. All unloaded and distributed from the huge ships that came up the Thames up to Tower Bridge or stored in the vast network of Warehouses on both sides of the Thames. Three-quarters of the butter, cheese and canned meat needed for the capital was stored here.

There has been a Roman Catholic Church on the site of the Most Holy Trinity Church since at least 1773 and it was the first church to be built fronting a public highway since the Reformation.

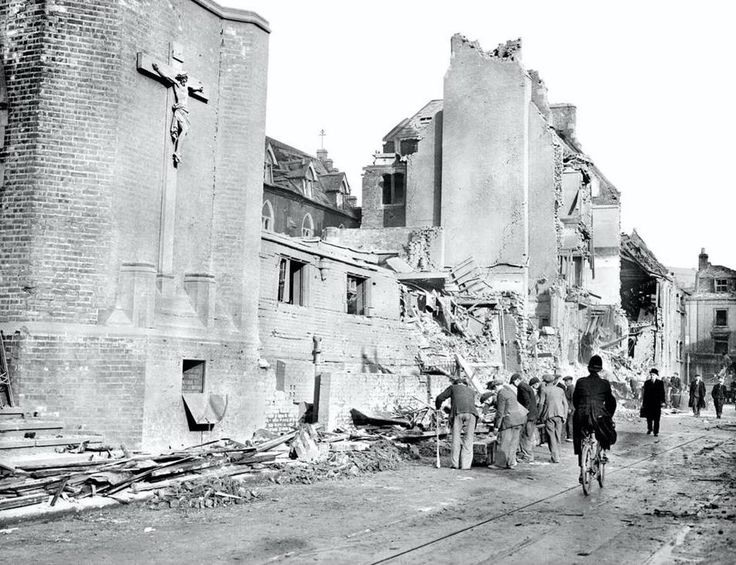

Dockhead suffered terribly during the Blitz in WW2 due to its proximity to the Docks. Between 7 October 1940 and 6 June 1941, 126 high explosive bombs and 2 Parachute Mines were dropped on the area (https://www.bombsight.org) and in December 1940, the Church was destroyed in a bombing raid. Sadly, five years later, just before the end of the War on 2 March 1945, the Priests’ House was also bombed and three of the four Parish Priests were killed. The fourth was badly injured and rescued only with great difficulty. His rescuer, a milkman, received the George Cross. The adjoining Convent of the Sisters of Mercy was also damaged but with no loss of life. I can’t help thinking that my family must have known the Priests and were almost certainly members of the congregation.

But the Church was eventually rebuilt and the present polychromatic brick building (first illustration above) was designed by H.S. Goodhart-Rendel and completed in 1959. The modern building was designated Grade II Listed but was upgraded to Grade II* in 2015.

The Church features heavily on my Maternal family tree. So far, I have found 12 marriages and 3 Baptisms at the Church from 1852 to 1931.

The furthest back of these is the first marriage of my 2 x great Grandmother, Hannah Lyons, who married a Michael Taylor there in 1852.

Hannah was born in Ireland in the early 1830s (not sure exactly when) and was living in England by the time of her marriage to a Michael Taylor in 1852.

It may have been that Hannah’s family came to England a s a result of what became known as “The Irish Potato Famine” between 1845 and 1852 when almost 2.2m people mostly from southern and western Ireland emigrated to England or America following the failure of the potato crop on which they depended, predominantly due the infection of potato crops by a blight that affected crops in other countries in Europe as well. Over 1m people starved to death in Ireland alone.

Hannah and Michael continued to live in Bermondsey and had three children. Johanna who was the mother of the Kalaher orphans who were the subject of an earlier blog post on here (see link below), John and Julia who was my great grandmother.

Michael Taylor died in 1874 from Bronchitis (not unusual then in this damp area around the London Docks) aged 46.

Hannah remarried a couple of years later to a Thomas Sullivan but by 1891 Hannah is again a widow. Hannah’s two younger children, John and Julia, are still with her but by then Hannah’s other daughter, Johanna and her husband had both died leaving their children orphaned and Hannah has taken three of them to live with her.

On the 1901 census, Hannah is living with her youngest daughter Julia and Julia’s husband and she died just a few months later aged 65.

Both Hannah and Michael’s daughters, Johanna and Julia married at Holy Trinity (Julia giving birth to her first child just five days later) as did Julia’s daughter, also called Hannah (my grandmother) two of her other daughters and her son who were all my great Aunts and Uncles.

I can’t find any photos of my Grandmother and grandfather’s wedding (perhaps there weren’t any …) but here’s the little family they made including my lovely Mum, Marie and her sisters Hannah (this Hannah was baptised at Holy Trinity too) and Eileen plus Hannah’s husband enjoying a day at the beach I’m guessing in the late 1940s, perhaps early 1950s.

Thank you for reading this and I’m sorry I’ve been away so long ❤️