I want to tell you a bit about Lily’s family. The Thatchers. And to finish Lily’s story. But first a cemetery.

My family research has generally revealed poverty. My forebears lived in dirty, damp conditions, engaged in hard, manual work. Generally living hand to mouth, day by day. When they died, they were buried in unmarked, public graves. No headstone. No memorial. After 50 years or so, the land in which they were buried, reverted to public ownership and someone else was buried there.

Rarely have I found a headstone or memorial in existence.

But not the Thatchers. There is a family plot in Mont à l’Abbé cemetery in St Helier in Jersey for all of them. And headstones. All of them together. With marked graves. It is simply a family historian’s joy to find such things (Reader – wrong word to use about death I appreciate but you know what I mean I’m sure …)

Mont a l’Abbé cemetery is in two parts. The first was opened in 1855 (known as the Old Cemetery) with the “New” part being added in 1881. It is a vast and very peaceful place which is high up and overlooking the sea in St Helier. Plots are divided into four (north and south 1 and 2). The Thatcher family has one whole plot.

Ida Thatcher was the first to be buried there in one of the graves on what is actually the East side of the plot (despite them being described as north and south) side of the plot. As I said in Part I, Ida died aged 14 in 1899 from Meningitis.

Also on this side is John Charles Thatcher, Lily’s father (and Ida’s of course) who died in 1922. Next Jane Ann Lawrens (sometimes spelt Laurens as you can see) , their mother and John’s wife, in 1924. And here they are.

You will see too, that there are two other burials on this side of the plot. Charles John Thatcher and Emily Kate Smith.

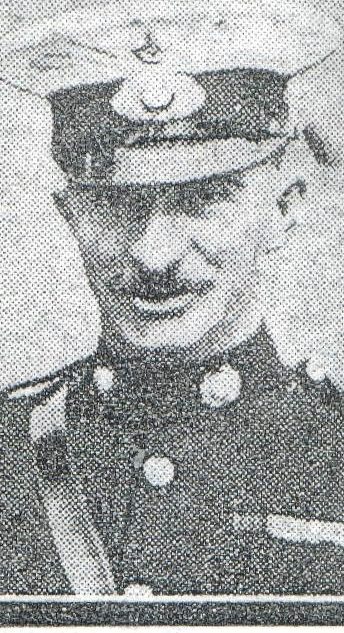

Charles John Thatcher (1883-1929) was the Thatchers first born child and Lily’s eldest brother. Charles joined the Royal Marines in 1900 when he was only 17 (he gives his age as 18). Charles signed up in Portsmouth to the Royal Marines Light Infantry (RMLI) and went on to have a long and distinguished career of military service which ended after 22 years (and of course spans World War I) when he was “retired” in 1922. Charles achieved the rank of Regimental Sergeant Major and was awarded the Victoria Cross, the Distinguished Service Medal and Distinguished Service Cross in 1918. In addition, Charles’s record confirms the award of the Meritorious Service Medal which was given to senior non commissioned officers for long and/or distinguished military service.

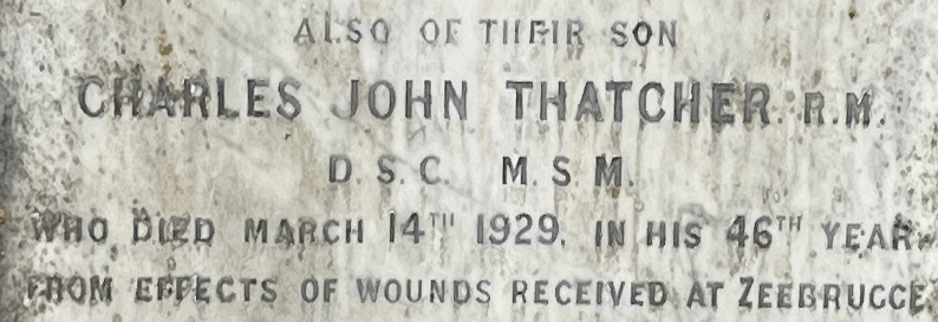

This is a magnified copy of the inscription on Charles’s gravestone where it attributes his death to wounds received in the battle of Zeebrugge in WW1.

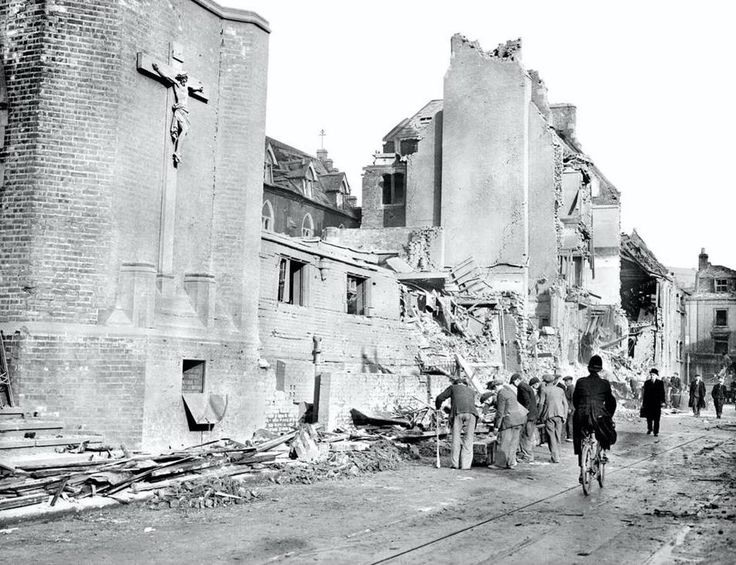

The Zeebrugge battle was fought in April 1918 when the British Navy attempted to stop German ships and U-boats from using Zeebrugge as a base from which to launch a raid on England. It was led by the 4th Battalion Royal Marines and the warships HMS Vindictive and Invincible. Charles’s record indicates he served on Vindictive in 1912 but in this campaign he was apparently on the Invincible.

If you’d like to know more about the Zeebrugge raid, this link will take you to a full account https://www.cwgc.org/our-work/blog/the-zeebrugge-raid-at-105-the-trials-tragedy-of-a-daring-amphibious-assault/

Charles was mentioned in despatches as follows “ Sergt.-Maj. Charles John Thatcher, R.M.L.I. was mainly instrumental in conveying the heavy scaling ladders from the ship [Invincible] to the Mole [The Zeebrugge mole was a mile-long seawall jutting out into the North Sea upon which several German sea-facing artillery guns were placed and had to be taken out for the plan to be a success. It was also studded with concrete machine gun posts] and throughout the operation displayed great coolness and devotion to duty” for which he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. I cannot find mention of Charles amongst the injured but when he died 11 years later several regional newspapers reported his death as a “Hero of Zeebrugge” and all the reports mention that Charles was severely wounded and gassed.

Charles was awarded the Victoria Cross for “Operations Against Zeebrugge and Ostend on the night of 22nd to 23rd April 1918” according to his Military Record and a report in the London Gazette in July that year.

Charles died in March 1929, aged 46. His Death Certificate says he died from Pulmonary Tuberculosis and Asthenia (generalised weakness or lack of strength). Charles’s family had inscribed on his gravestone that he died “from effects of wounds received at Zeebrugge”. Whether, in fact, cause and effect were ever established though is not clear.

However Charles does not have a Commonwealth War Grave. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) is very thorough in this respect and will ensure service personnel have a CWG memorial stone even if they died long after wounds or injuries received in conflicts if their death can be directly attributed to them, so it would be easy to conclude that this inscription is not necessarily accurate.

So I wrote to the CWCG. I explained what I had discovered and whilst I have not been successful at establishing either the veracity of the view that Charles died as a result of effect of his being gassed in WW1, nor of getting a CWG memorial for him, I did receive this rather lovely reply to my enquiry.

Unfortunately the Commission’s remit is limited to those who died within our qualifying date period for both the First and the Second World War. Rather than being an arbitrary date, 31 August 1921 is when the Act of Parliament was passed which formally brought the First World War to a conclusion, hence is used to define those who died during the war years.

I’m afraid that as this individual died in 1929, so after August 1921, he therefore falls outside of our Royal Charter responsibilities. There is no provision for us to make exceptions, even in cases where there is evidence that a post-1921 death was attributable to wartime service. Sadly many men died in the years immediately following the war and in the subsequent decades – some but not all will have been either directly or indirectly a consequence of wartime military service.

Whilst understanding that this outcome may represent a disappointment, equally, we hope you can understand the need to apply our Eligibility Criteria consistently. That this individual is not considered a Commonwealth war casualty within the remit of the Commission in no way diminishes the sacrifices made, nor the tragedy that his family had to cope with. We’re glad that through your efforts, Sgt Major Thatcher continues to be remembered.

The final commemoration on this side of the Thatcher plot is that of Emily Kate Smith (1890-1940). Emily was Charles Thatcher’s wife and they were married in September 1918 at the Royal Marines’ Barracks in Alverstoke in Hampshire by the Royal Marines’ Military Chaplain.

Emily was born in Crawley in West Sussex in 1890. When she and Charles married in 1918, Emily gives her address as Cowes on the Isle of Wight. In 1921 they are living in Military Barracks in Gosport in Hampshire. Lily, Charles’s sister, was one of the Witnesses.

Emily was the sole recipient of her husband’s estate when he died at which time they were both living on Jersey. They had no children. Emily died in 1940 aged just 50 from Colon Cancer.

Emily’s Will is curious. Emily leaves her entire estate to an Alison Eleanor Coffin who was only 13 when Emily died. The Will notes that Alison is the daughter of a René Armand Coffin to whom the estate would have gone if Alison were to be deceased when Emily died. Emily’s Will was made just 6 months before she died.

So now I’m curious about the Coffin family of Jersey. I want to know what René and his daughter’s connection was to Emily Smith and why she chose to leave her entire estate to this child. That’s how genealogists get distracted …

Reuben Lawrence Thatcher (1887-1969) was Lily’s younger brother; only two years separated them. Reuben never married. Reuben worked in his Father’s painting and decorating business and from trade records over the years, I could deduce that he took over management of the business after his Father died.

Reuben served in WW1 in both the Royal Defence Corps and the Honourable Artillery Company. Reuben was discharged from the Army in 1918 after being gassed.

Reuben receives half of his Mother’s house in 1924 when Jane Lawrens died (Lily having received the other half). Reuben also receives various bequests of furniture and ornaments from Jane.

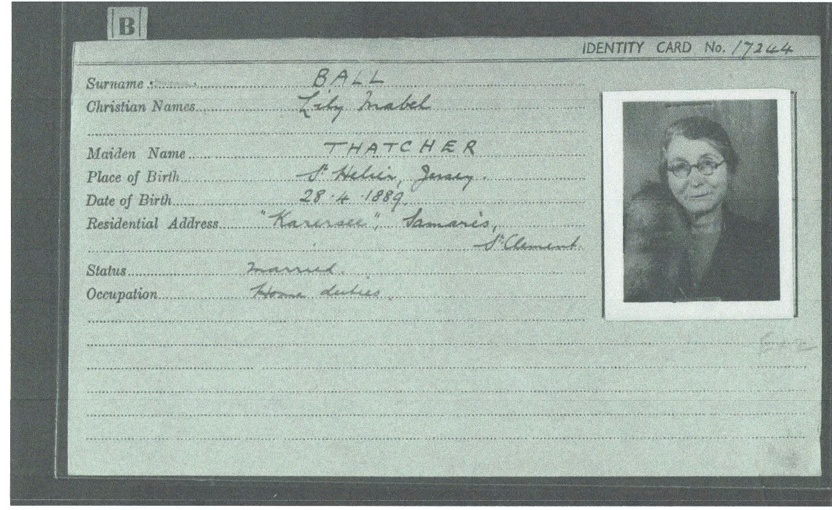

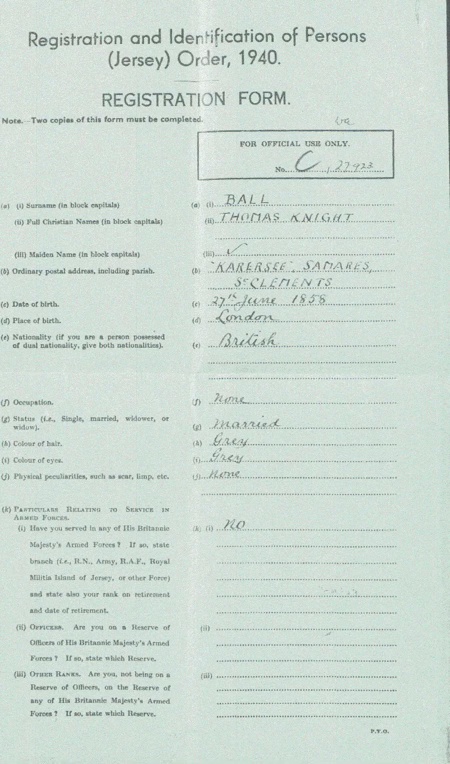

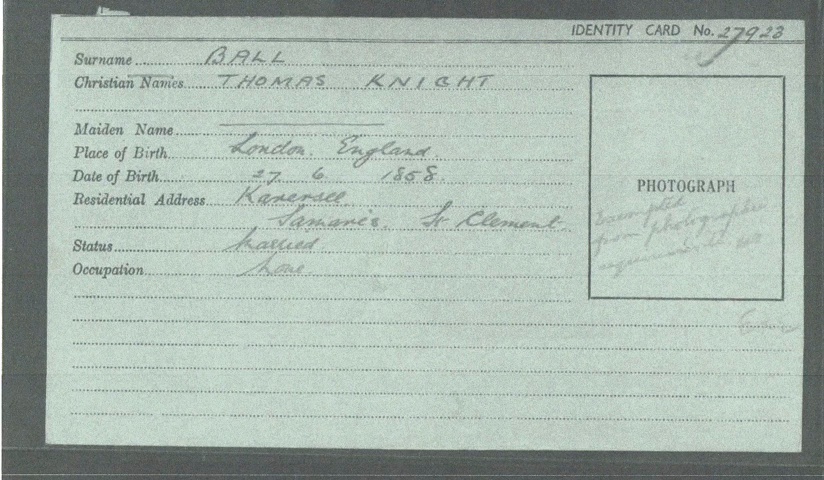

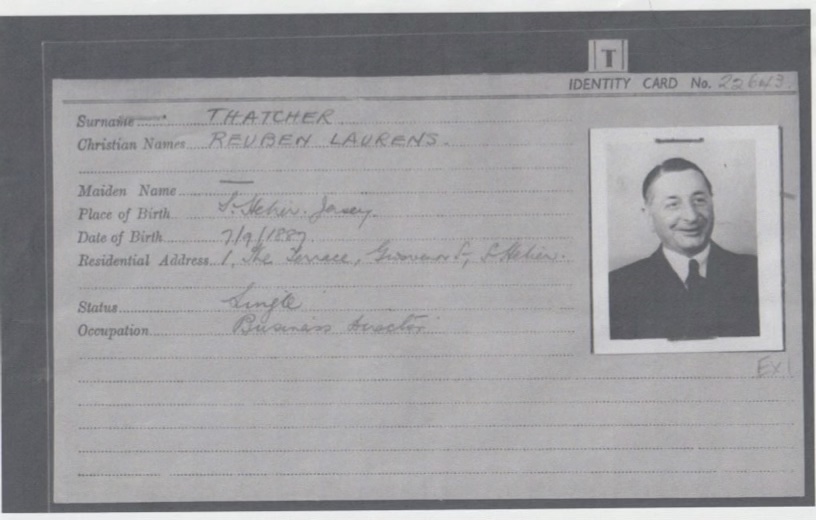

Reuben was living on Jersey during WW2 and thus also had a Registration card like Lily and Thomas.

Have you ever seen a happier face being presented to a hostile, occupying military force?

Like Lily, Reuben loved to travel and during the 1950s can be found on various ships’ passenger lists to and from the UK going to Buenos Aires, Canada, and extensively in the Far East including Yokohama in Japan.

Reuben died in 1968 aged 81. His Will is comprehensive. Probate records show his estate as being worth £42k (worth about £624k now). I think where he died (The Limes, Green St., St Helier) was a nursing and residential care facility for older people.

Reuben’s burial record shows his funeral was held at St Helier Parish Church on Thursday 2 January 1969. Reuben was cremated and his ashes are buried at Mont-a-l’Abbé cemetery in the Thatcher family plot and commemorated on the same stone as Lily, his sister and Thomas her husband.

Reuben left the individual bequests of between £100 and £250 each to Charity and good causes with some personal bequests to individuals. These are detailed on his Will as follows

- Jersey Blind Society

- Brig-y-Don Children’s Convalescent Holiday Home, Jersey

- Jersey Masonic Temple

- Eunice Callas de Caen wife of Francis de Boutillier of Highfields, St Ouen, Jersey

- Christopher Le Boutillier grandson of Francis Le Boutillier

- John Wilcox son of John T.A. Willcox

- Jane Wilcox, daughter of John T.A. Wilcox

- Mary Wilcox

- Sarah Wilcox

– The last four above named to receive all Reuben’s books, prints and pictures

- Richard Loughlin, Head Steward the United Club, St Helier, Jersey

- Philip Edgar Le Couteur, 6, Rouge Bouillon, Jersey

- Walter F Thatcher, The Follies, Pontiac Common, Jersey [presumably a paternal relative]

- Fred Percy Tastevin, Avenue House, West Park, Jersey

- Remainder to Lily, his sister

Should Lily have predeceased him (she didn’t) there were further instructions about how her share should also be divided between charities.

So this is a further bequest that went to Lily in addition to the one from her mother and from her husband.

And finally to finish Lily Mabel Thatcher’s story.

In Part I, we left Lily just after her husband, Thomas, died in 1948. After Thomas’s death, I have found Lily once again on various ships’ passenger lists travelling around the world during the 1950s.

Lily died in 1976 aged 89. She is the last of John and Jane’s family. Lily’s estate was worth over £1m at the value of today’s currency. While that itself is quite staggering, it is the breadth and extent of the distribution of her estate which is extraordinary.

Lily appointed the Midland Bank as her Executor and her entire estate is divided up between individuals and charitable causes.

This is a distilled, version of Lily’s Last Will and Testament.

Lily begins by specifically stating that she wishes to be buried in “her grave” at the New St John’s Cemetery at Mont-à-l’Abbé with her husband, Thomas Knight Ball (which she is). They are both in Block V Plot 15 on the opposite side of the family put from her parents and elder brother. The gravestone also includes a memorial to Lily’s younger brother Reuben who was cremated and his ashes scatted on Plot 15.

Lily asks for her body to be repatriated to Jersey should she die elsewhere and she specifically instructs that she must be buried wearing her wedding ring.

Lily also leaves money in trust for her parents’ graves and hers and Thomas’s graves to be upkept in perpetuity.

- To Mr and Mrs John Tooke-Kirby of Goring on Sea the sum of £20,000

- To her godchild David Tooke-Kirby £10,000 when he reaches 31

- a Mrs Iris Laurens of “Iona” Greve d’Anette, St Clement, Jersey [a maternal relative on her mother’s side] £10,000 plus all Lily’s jewellery (specifically including “her five stone engagement ring and her solitaire diamond ring) and clothing with the exception of her gold bangle (see below)

- Miss Gladys Marett of Overseas Flats, Dicq Road, St Saviour, Jersey £3,000

- Mr and Mrs George Falle of 6, Beach Crescent, St Clement, Jersey [Lily’s mother Jane Laurens had a sister who married a man called Falle so presumably this was a maternal relative] £3,000

- a Mr and Mrs Harborow of “Larmona” 65 Cleveland Gardens, Golders Green, London, NW2 £3,000 plus to Margaret Harborow, Lily’s gold bangle presented upon her retirement from Lloyds Bank, Lombard Street

- Mr and Mrs Stanley P Le Ruez of “Freshwinds”, Bon Air Lane, St Saviour, Jersey £3,000

- Miss Amy Le Cornu of “Hengistbury” Claremont Road, St Saviour, Jersey £1,000

- Mrs R Le Templier of 8, Cleveland Avenue, St Helier [the address where Lily died] £1,000

- Mrs Gwen Talbot c/o Mrs Templier above £500

- Dr and Mrs Norman Pitts of Red One Montauk Avenue, Stonington, Connecticut 06378, USA £2,000

- Dr Barnardo’s Homes £4,000

- the Jersey Blind Society c/o La Motte Chambers, St Helier, Jersey £5,000

- St Dunstan’s (the organisation for men and women blinded in war service) £7,000

- Brig-y-Don Children’s Convalescent and Holiday Home, Samares, St Clement, Jersey (to which her brother, Reuben had also left a bequest) £5,000

- Cancer Research £7,000

- Invalid Children’s Aid Association £7,000

- The Home for Aged and Infirm Women known as “Glanville”, St Mark’s Road, Jersey “for providing amenities for the patient’s use” [probably means Lily was in there at some point] £7,000

Finally, Lily says any residue should go to the Jersey General Hospital in memory of her parents and her late brother, Reuben for the purpose of building a home, hostel or homes for old people in need to be called the “Knight Ball and Thatcher Home” or to extend the Jersey hospital with a ward or annexe to be known as the “Knight Ball and Thatcher Ward”. I have visited the hospital and no such ward exists. Nor could I find a facility for elderly people of the same name. so what happened to that bequest is a bit of a mystery.

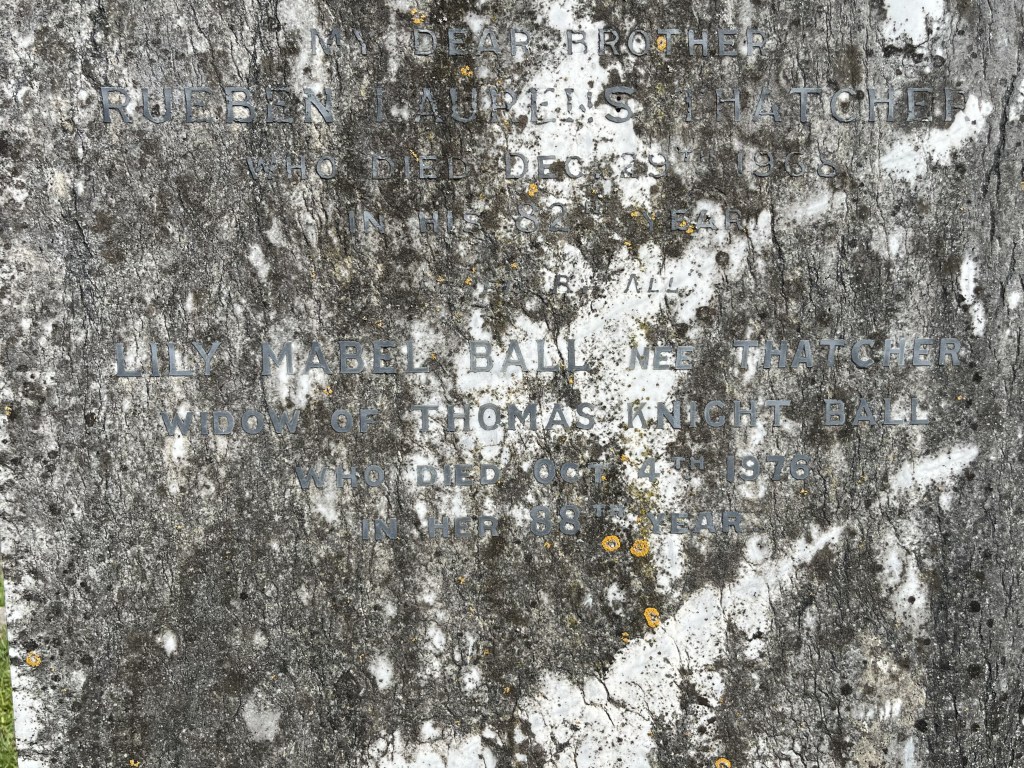

What a woman. Lily did such a lot of good with her bequests. I have visited the Thatcher family plot and shown you above a photo of the graves on the East side. Unfortunately, it is the Western side that gets very degraded by the weather and because of this, the gravestone is very, very hard to read. But I could make out some of the writing and it is clear enough that Lily and Thomas are buried there and there is specific mention of the stone also being a memorial for Lily’s brother, Reuben.

So there they all are. The Thatchers. Lily was the last of them. Not my relatives but nonetheless incredibly interesting I think (I hope you do too).

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading this and thank you for visiting my site.