It all started by chance. Probably that’s the best way for intriguing tales to start.

As well as my own research, I also sometimes do it for other people. The Barkel family is for my lovely Mother-in-law born Margaret Barkel Lilley. Margaret Swinburne since 1950, is still dispensing wisdom at 97 and is a rich source of information for her family with her sharp and insightful mind and a memory as sharp as a steel trap.

Margaret’s family come from the North East of England. Mining stock. Hand to mouth existence. Poverty. Hard back breaking work. Small cramped houses. Tight communities all looking out for one another. Margaret remembers that. Margaret lived that. One day I’ll write Margaret’s story but today it’s her 2nd cousin, Albert Valentine Barkel.

Margaret is still in touch with an ever diminishing family circle back in the North East. One day, during a phone call, one of her relatives said she had seen a name that had caught her eye on a Memorial Board for those who had fought and died in both World wars in a local church in the North East and wondered if he was a relative.

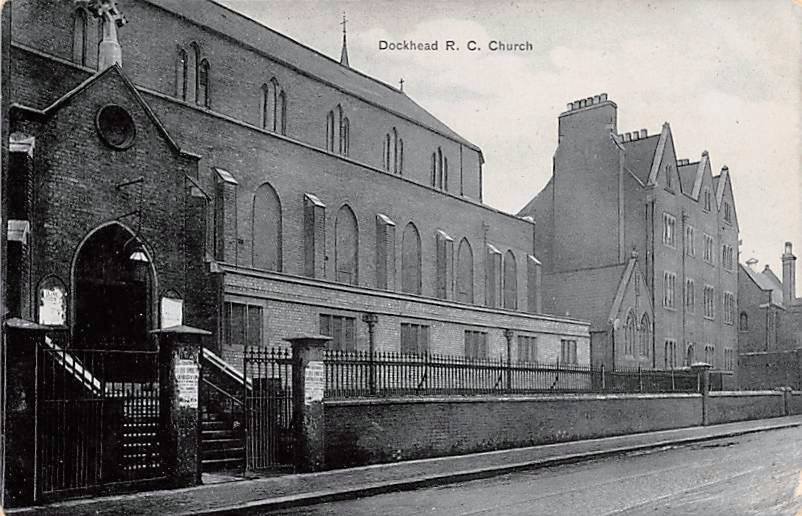

The Board was in St Paul’s Church in Ryhope. Ryhope was once a small pit village to the south of the city of Sunderland in Tyne and Wear. Nowadays it feels like it’s just one of a number of suburbs of Sunderland and kind of morphs into the city.

The name was Albert Valentine Barkel and Margaret assured her relative that “our Lin” (that’s me) would find out.

So I did. And a gem of a story it turns out to be …

Albert was born in San Francisco, California, USA on 14 February 1912 (well, there’s the answer to his unusual middle name, right there). I will admit, the place of his birth was a bit of a surprise but this is how it came to be.

Albert’s parents were Thomas Deaton Barkel (1888-1971) and Hilda Alice Cowley (1886-1928). Thomas was born in Ryhope, then a small mining village in County Durham and Hilda at a nearby village called Milfield. Thomas and Hilda married in the Summer of 1906 in Durham.

Life then seems to have taken a downward turn very quickly for Thomas and Hilda though when, later in 1906, Thomas was tried with two others for the manslaughter of a man called McDonald Dumon in Durham. Thomas was working in a Bar at the time so maybe a pub brawl that got out of hand. Thomas and his co-defendants were acquitted.

In December 1906, Thomas and Hilda had their first child. A son, called Albert after his paternal Grandfather, born in December (so Hilda would have been pregnant when they married). But little Albert died soon after he was born.

Next, in 1908, they had a daughter, Annie, named after her paternal Grandmother and in 1909, they have another son, called Thomas Deaton Barkel after his Father. Happily, Annie and Thomas junior survived.

On the census of 1911 which was taken at the beginning of April that year, Thomas senior was working as a Coal Miner in the Ryhope Colliery and Thomas, Hilda and their son are living at 18, St Paul’s Terrace in Ryhope.

Their daughter, Annie, however now aged 3 was living nearby with Thomas’s parents, Albert Barkel and Annie Forster.

But, later that year, Thomas and Hilda went on a grand adventure when they left County Durham and boarded the SS Celtic in Liverpool, bound for New York city in America. They only took their son, Thomas, however and little Annie stayed with her paternal Grandparents.

Thomas, Hilda and Thomas jnr arrived at Ellis Island in in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty on 21 October 1911 presumably in the hope of making their fortune like so many others around that time.

The passenger manifest records that Thomas was 23, had dark hair and grey eyes; was 5 feet 7 and a half inches tall and had a dark complexion. The contact in the country Thomas and Hilda had left (called the “Old Country” on the US immigration form) was given as Albert Barkel (Thomas’s father) who lived at 14, Thomas Street, Ryhope.

Thomas said that he and his little family were bound for San Francisco, California and the record states that Thomas had £150 in cash on him (quite a lot of money in 1911).

How they came to be making this journey will no doubt remain a mystery. It is as baffling as it is exciting. Ryhope was a very small place at that time (and for a long time afterwards). The only thing people did in the village was work in the local coal mine and go to Chapel on a Sunday (sometimes twice). Everyone knew everyone. Just what preceded Thomas and Hilda’s decision to set out from North East England not only to the USA, but not to stop at the East coast there like so many did, but to continue to travel West and go all the way to California.

But go to San Francisco they did. And they made a life there including having their next son, Albert Valentine in February the next year (so Hilda must have been pregnant when they set off from England).

After 6 years, Thomas, Hilda and their eldest son became US citizens via the US Naturalisation process in December 1917. Albert already was a citizen by virtue of being born in the US.

That same year, Thomas Snr was drafted into the US Forces (to serve in WW1 presumably but there are no records I can find to show whether he actually went to fight).

On the US Census of 1920, taken on 1 January 1920, Thomas, Hilda and their two sons are living at 1822, West 29th Street, San Francisco, California, US. Thomas is working as a Storage Man at an Ice Cream Factory and Hilda is working at the same place as a “Wrapper”.

In April 1920, Thomas and Hilda apply for and are granted US passports.

They have now been in the US for 9 years. They have a house, jobs, two sons, they are all US citizens. Thomas has even served in the US military.

And yet just two months after they get their US passports, Thomas, Hilda and their two boys board the SS Imperator of the Cunard White Star Line and come back to England where they land at Southampton on 26 June 1920.

What made them leave, I wonder? I could conclude they only got the passports to travel back to England. But when they got there it doesn’t seem as if they had made their fortune and had come home to set up a(nother) new life because, the next thing I can find is Thomas, Hilda and their two sons on the 1921 UK Census taken in June 1921 so about a year after they came back to England when the Census return shows that they are living with Thomas’s parents, Albert Barkel (1865 – 1951) and Annie Forster (b 1869) at 40, Thomas Street, Ryhope.

Albert was a Time Checker at the coal mine in Ryhope and Annie a housewife. Thomas and Hilda’s daughter Annie is still there, now described as an adopted daughter and now aged 13. Annie Forster’s parents a Thomas D Forster who is a retired Coal Miner formerly working in the mine at Ryhope and his wife Emma are also living at the address. They are aged 74 and 72 respectively.

The houses in Thomas Street are not large. Never have been. And there were 7 adults and two children living in number 40. That would seem to underpin my view that Thomas had not come home with a heap of money.

Thomas is now working as an Attendant at the local Mental Hospital, Cherry Knowle, and Hilda is a Housewife. Their two boys now aged 11 and 9 are at school.

Then 7 years later, Hilda died aged just 42 in 1928 and in 1929, Thomas married a Frances Ward (1891 – 1980) in Sunderland.

On the 1939 Register, Thomas, Frances and son Albert Valentine are living at 12, Stockton Road, Ryhope, Sunderland. Thomas is now described as a Male Nurse at Cherry Knowle and is also an ARP Warden. Albert Valentine is an Acountancy Clerk.

Thomas lived to be 83 and died in Sunderland in 1971. Frances died in 1980 aged 88.

Thomas and Hilda’s eldest son, Thomas Deaton Barkel jnr married a Violet Sedgewick in 1929, became a Police Officer and died in 1980.

I cannot find anything out about their daughter Annie after the 1921 census.

Albert Valentine Barkel, Thomas and Hilda’s youngest son, married a Beatrice McMullan in 1941 and joined the RAF Reserve, serving in Bomber Command where he achieved the rank of Flight Sergeant and was posted to RAF Wymeswold in Leicestershire.

On 7 October 1942, Albert and two colleagues were taking part in a training flight. Albert was the Navigator and the plane they were flying was a Vickers Wellington Bomber, designed in the mid 1930s specifically to carry out medium to long range bombing missions.

At 16.08 that day, the plane was seen jettisoning fuel just before it crashed at Woodhouse Eaves, 3 miles south of Loughborough.

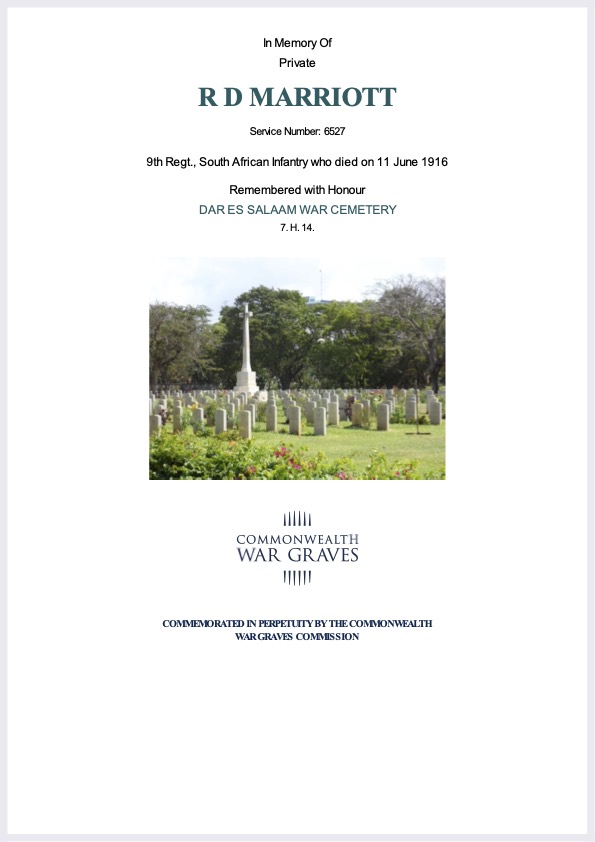

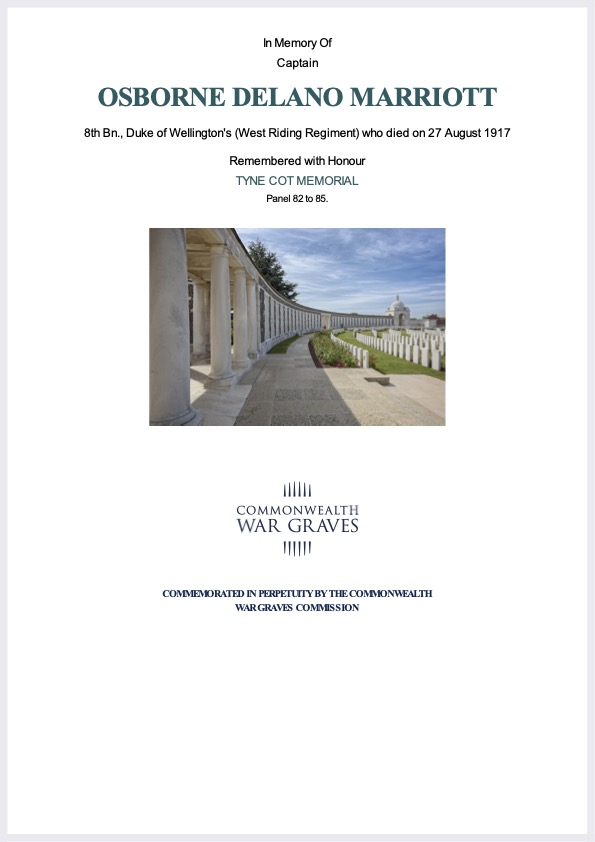

All 3 men on board were killed. Albert who was 30 plus Warrant Officer Donald Anthony Gee and Flight Sergeant Leslie Jones who were both 22.

Albert is buried in Sunderland Cemetery in Ryhope Road, County Durham and his grave is provided and maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

The inscription on his grave reads “In Proud Remembrance of my Husband”.

The National Probate Register records that Albert left £164 12s 4d to his wife, Beatrice, who lived at 32, Waldon Avenue, Ryhope, County Durham.

Albert’s name is included in the memorial in St Paul’s Church, Ryhope commemorating those from the area who died in WW2.

Linda Swinburne Family History Blog

Proudly powered by WordPress