In this week of International Women’s Day, I thought it would be appropriate to celebrate women who have taken a stand.

When my maternal great grandfather, John Cownley, completed the Census in Bermondsey, Dockhead in 1911, he noted that three of his six children worked in factories locally.

All of those were his daughters. One of those daughters was my grandmother, Hannah.

My grandmother was just 14 and working as a “Factory Hand – Labeller, Drugist”, her older sisters Mary Ann, 17 and Lizzie, 16 were working as a “Tin Worker” and a “Book Folder” respectively.

Descriptions of factory working give us a fascinating insight into early 20th century life in Bermondsey.

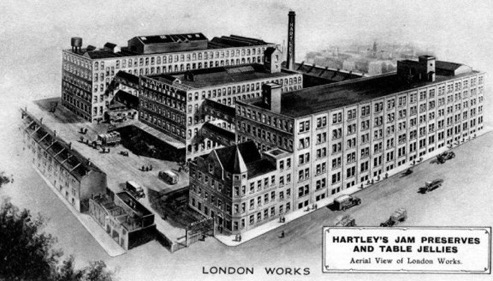

At that time, Bermondsey was famous for manufacturing trades that were based there. Jacobs Cream Crackers, Cross and Blackwell, Hartley’s Jam (employing 1,500 people), Pinks Jam, Courage Beer, Spiller’s dog biscuits, Sarsons Vinegar, Shuttleworths Chocolate, Liptons Tea, Pearce Duff Custard Powder and Confectionery and Peak Frean Biscuits (probably the biggest employer in the area at 2,500 workers) were among the Bermondsey factories of which there were over 23 in 1911.

Also, the manufacture of metal boxes – like tins for holding baked beans and biscuits for example – was also carried out in Bermondsey. My great Aunt, Mary Ann mentioned above probably worked for a company called Wyatt & Co., one of the biggest tin manufacturers in Bermondsey at that time. The factory was in Tanner Street, SE1 so not far from where the Cownleys were living in 1911 and the building was not demolished until the 1950s.

Staggeringly, there is still a wooden sign in place today that belonged to Wyatt & Co despite the immense redevelopment that has taken place in the area over the last 50 or 60 years.

Work in all the factories was hard, dangerous, poorly paid and mostly done by women (supervised by men who – it was ever thus – earned more than them). Most men, though, worked in heavier industry in the Docks or digging the roads. In the tin factory, women often lost fingers on unguarded machinery and cheap glass was used in the jam factories causing it to explode sometimes when the hot jam was poured in causing injury and sometimes blindness to the women on the production line.

The factories were not always small and cramped though. The Hartleys Jam Factory site, for example (which I mentioned in my last Blog at Christmas) was huge but not very mechanised. Instead it relied on thousands of cheap, mostly female, workers to do endlessly repetitive tasks to produce their jars of jam.

Most women earned less than six shillings a week and those under 16 earned as little as three shillings. My Grandmother, at 14, would have been one of the lower paid workers.

There had been no history of factory workforce unionisation however, unlike in the Docks where over 100,000 workers had gone on strike in 1889 winning recognition for and unionisation of casual labour.

But that Summer of 1911, all that changed. The Summer was a hot one. With no means of keeping food cool it went off quickly meaning families had less to eat than ever and child mortality had risen sharply over the Summer months.

The Docks and Railway workers had been on strike for weeks nationally, including London, over working conditions and Troops had been brought in, leading to two young pickets being shot dead in Liverpool in the ever increasing strain of the Summer conditions.

Into this hotbed of tension stepped two female trade unionists, Ada Salter and Eveline Lowe (until very recently (2003) there was a school in Southwark called after Eveline Lowe), who formed and convinced hundreds of women to join, the National Federation of Women Workers (the NFWW).

The NFWW called a rally in Southwark Park at which Emeline Pankhurst, the leader of the quest for female suffrage, spoke as well as Ben Tillett, the leader of the Dockworkers’ Union. Quite out of the blue and to everyone’s surprise, on 15 August 1911 at 11 am, over 20,000 women downed tools in the factories and went on strike. Factories ground to a halt. The manager of the Peak Freans’ biscuit factory was quoted as saying “I don’t know of a single business that is working in the district… It is a reign of terror”.

The Manchester Guardian carried a report of the action the next day (16 August 1911). The reporter noted,

“At the [Bermondsey] jam works, work really is work. The women frequently have to carry three gallon jars of hot pulp long distances around the factory”. And in the same article, “There are more women workers in Bermondsey than in any other part of London”.

Ada and Eveline appear to have been so successful by making the women aware that if they came out on strike they would not be without assistance. Ada set up food depots and kitchens all along the river right from London Bridge down to Woolwich to help the Dockers and the women while they were on strike. In addition, the NFWW launched an appeal for funds to help the women. It raised over £500 in one week plus six barrels of Herrings (perhaps pickled at Pickle Herring Street where Elizabeth Regan had lived) (see my blog of 25 August 2020)

Then, towards the end of the Summer, Dockers in London began to be offered settlements by the Port of London Authority (increased wages mostly) if they went back to work. But they wouldn’t. Not until the women’s grievances were dealt with satisfactorily too. So, for the first time ever, men and women stood together as equals for fair working conditions.

It worked. After several weeks of the factories’ strike, the women were offered and accepted increased pay at nearly all the Bermondsey factories. Of the 21 factories on strike, 19 won substantial wage increases and in most, an end to piece work whereby workers were paid only by the number of finished products they produced. At Pinks the jam factory, which was the last to settle, the weekly wage rate rose from nine shillings to eleven shillings. A massive victory. Most factories resumed normal working by 8 September 1911

I had never heard of this strike, which became known as “The Bermondsey Women’s Uprising”. I find it thrilling that my Grandmother and my great Aunts are very likely to have been part of this event and may even be in the photograph below …

Up the women eh?

ps. sorry I’ve been a bit quiet. I’ve been rearranging my 20+ years of Genealogy research into a new filing system. It’s taken longer than I thought …

It’s bloody good xxx

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike

This is so interesting. Well done those women!

LikeLike

You could write a novel based on these fascinating stories.! Really enjoyed the blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I could … glad you enjoyed it x

LikeLike